While the use of cryptocurrency within Syria has often been discussed in relation to funding opposition groups, such as Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), recent investigations show that it also had relevance to the Assad regime.

The Crystal Intelligence team has discovered the existence of documents which reveal that the Assad intelligence services confiscated a sizeable volume of crypto from prominent online pro-Assad activists who are wanted by the FBI.

Seizing cryptocurrency from pro-Assad online activists

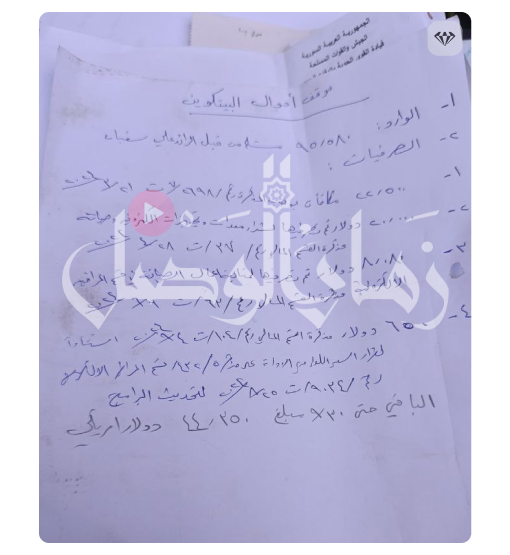

Crystal discovered a leaked document dated March 21, 2024, written by the Syrian Air Force Intelligence Directorate which reveals how the regime used confiscated cryptocurrencies for operational purposes.

The memo, addressed to the head of the Air Force Intelligence Directorate, Major General Qahtan Khalil, details the confiscation of cryptocurrencies from Firas Nooruddin Al-Dardar and Ahmed Omar Tamri Al-Aga.

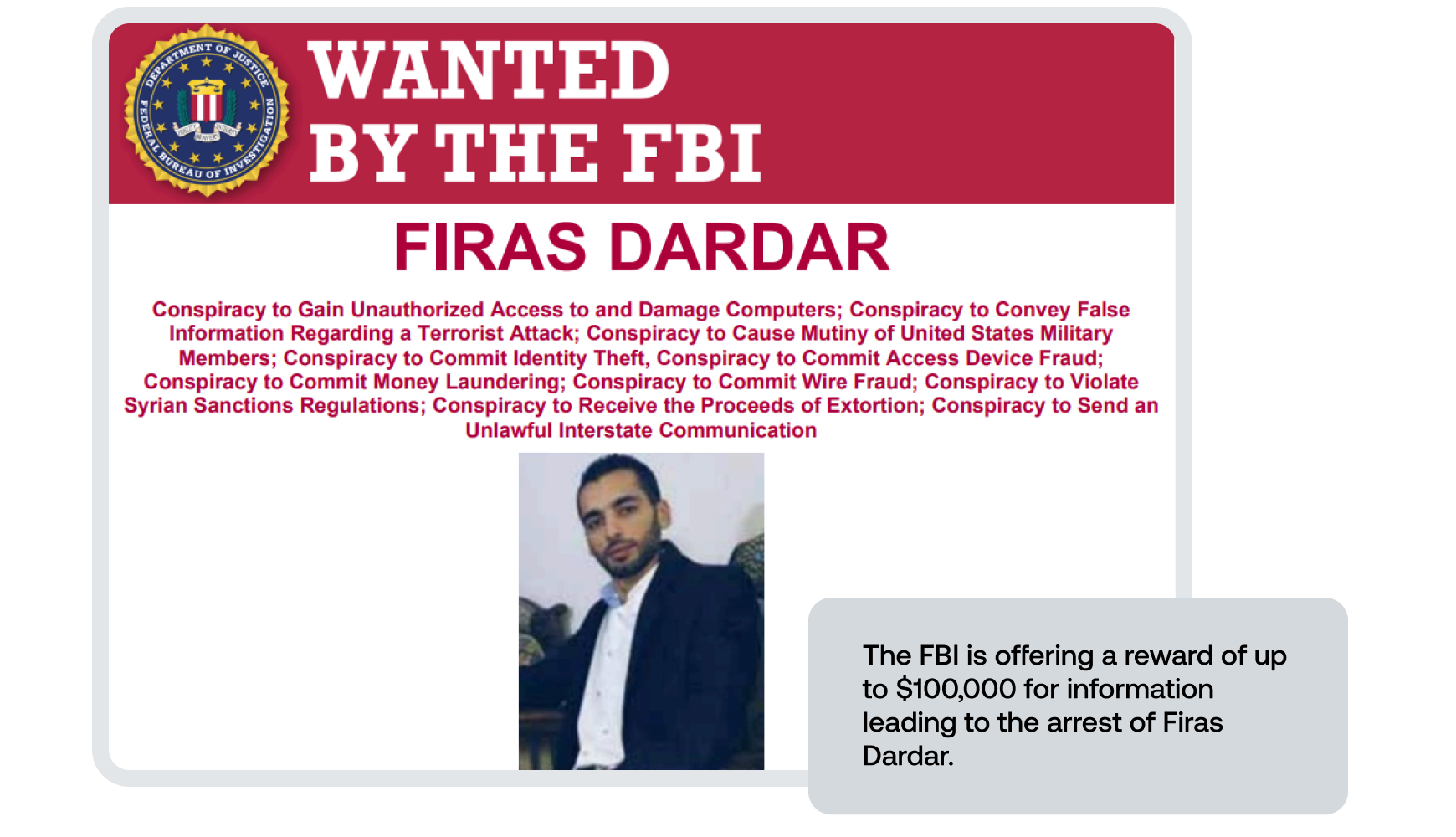

Further research identified Firas Nooruddin Al-Dardar as a key figure linked to the Syrian Cyber unit, which reportedly engaged in cyberattacks supporting the regime.

Al-Dardar is wanted by the US for his alleged involvement in cyberattacks between September 2011 and January 2014, during which he is accused of conducting dozens of attacks against American government institutions, media organizations, and private entities.

Consequently, the FBI issued a most wanted notice on Al-Dardar, with a $100K reward on offer for information which led to his arrest. Although it is not clear why the funds were confiscated from these individuals, it is striking that both Al-Dardar and Al-Aga had previously conducted cyber-attacks in support of the Assad regime, which led to them being wanted by the FBI. Separate research showed that these individuals had, since the warrant had been issued at least, turned against Assad and allied themselves with opposition forces.

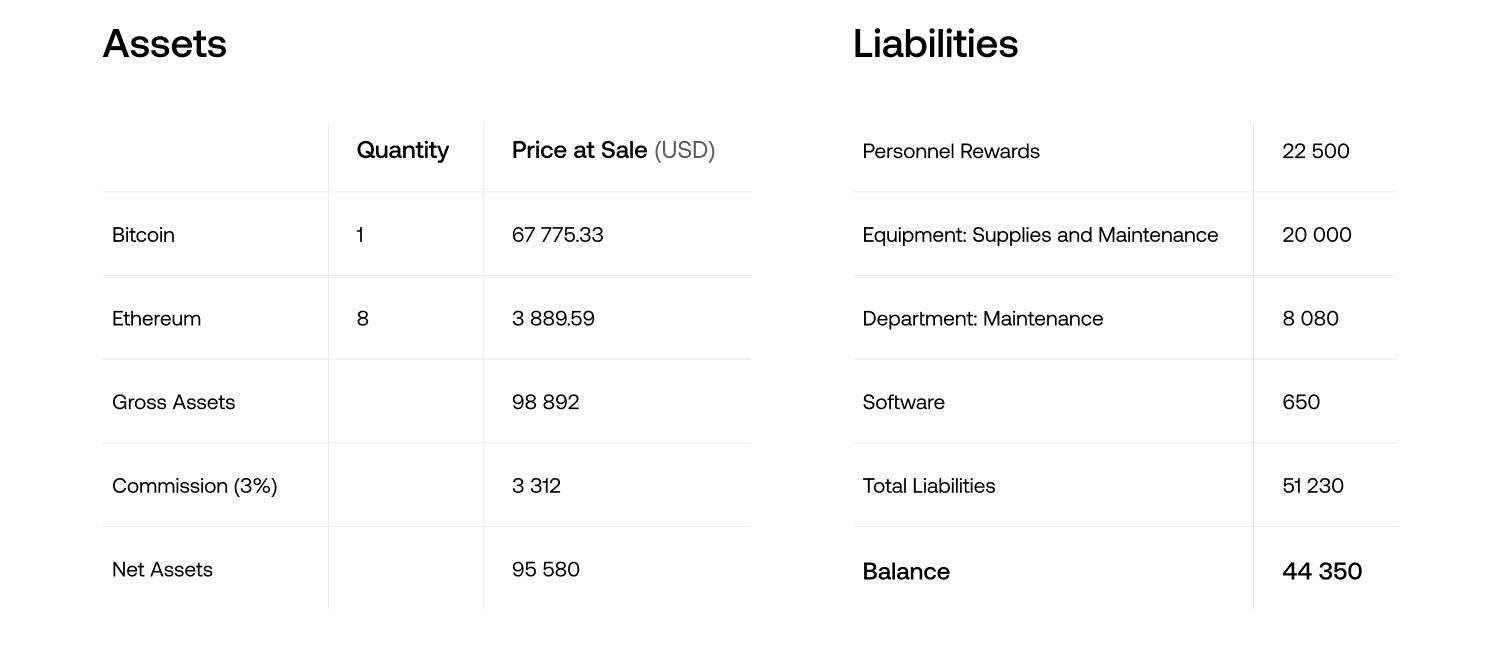

The document (pictured below) shows that the regime planned to use the seized digital currencies—1 Bitcoin and 8 Ethereum—to support the Directorate’s operational activities. The report outlines how these digital currencies were sold through an intermediary, Saud Al-Safadi, at approved prices: $67,775.33 per Bitcoin and $3,889.59 per Ethereum, with a 3.5% commission.

Above: Memorandum Addressed to the Major General, Director of the Air Force Intelligence Directorate, under the Syrian Regime

View the full FBI ‘Wanted’ poster here.

A hand-written note (below) included in the intelligence leak indicates that the funds from the sale of these cryptocurrencies were used for various operational expenses. Specifically, $22,500 was allocated for personnel rewards, $20,000 for the purchase of equipment, electronic supplies, and maintenance, and $8,080 designated for maintenance within the Cyber Surveillance Department. The note concludes by adding that $650 was used for software updates and $44,350 remains out of the original amount of $95,580.

Above: The handwritten note explaining cryptocurrency expenditures

It is not clear what these specific expenses relate to, other than ‘personnel rewards,’ which is about 50% of the funds spent. Ironically, the funds were converted into US Dollars, which the Assad regime prohibited the Syrian people from using.

Sources and destinations on-chain

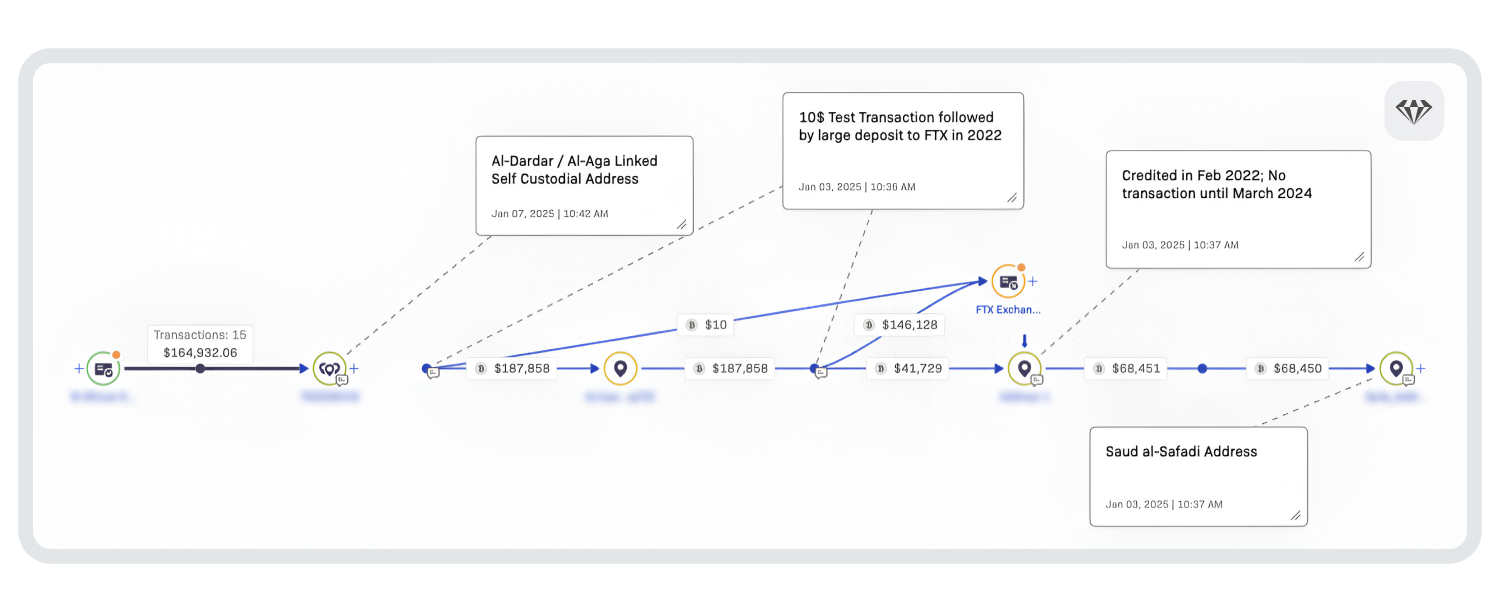

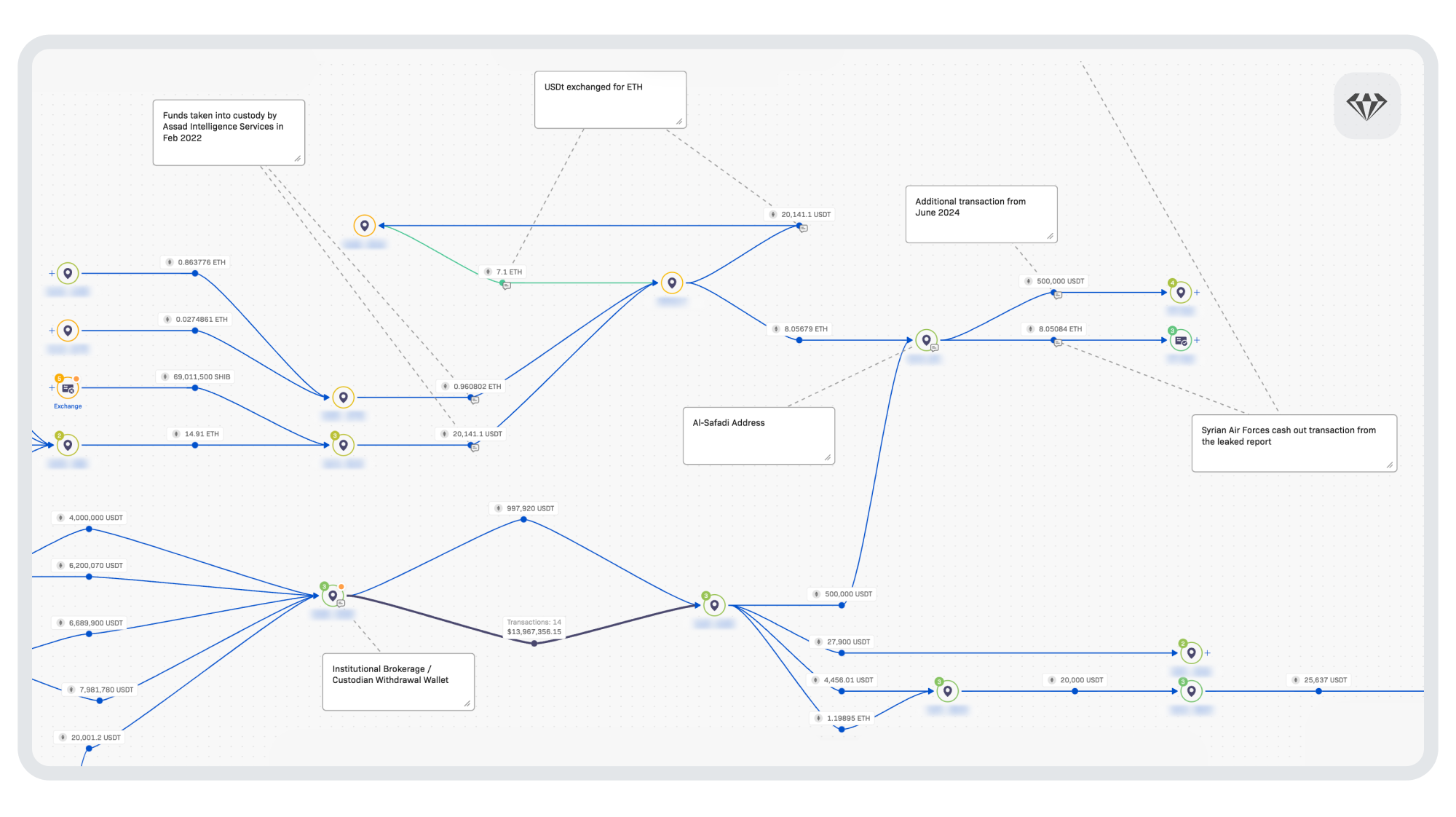

While the document alone is revealing in that it identifies the source of the individuals’ funds and the broker, we were able to enrich the investigation by looking at the activity on-chain using Crystal Expert.

Above: The on-chain source of funds analysis of Bitcoin confiscated by Assad Intelligence services

Firstly, the funds were likely originally confiscated in February 2022 and transferred to separate wallets. There was no activity on these wallets until March 2024, when the sale of the assets was mentioned in the document.

While it is unclear if the funds were connected to a wanted cybercriminal, Crystal Expert shows that most funds came from legitimate sources.

For example, 87% of the Bitcoin received was from exchanges that hold licenses in jurisdictions where cryptocurrency is regulated. In fact, most of those funds were from an exchange popular in West Africa. Additionally, we can see that a significant volume of funds was sent to FTX in 2022.

The Ethereum funds also arrived at the same exchange service, most likely indicating that they belong to the same account. The transaction timestamp confirms the information in the leaked documents took place in mid-March 2024. Analysis of the Ethereum addresses also shows the receipt of 500,000 USDT in early June 2024.

Above: The on-chain source of funds analysis of Ethereum and USDt confiscated by Assad Intelligence Services

The source of the 8 Ethereum appears to be a series of self-custodial wallet services, that engaged in general trading activity, purchasing and selling Shiba Inu, Link, and USDt.

The funds were confiscated in USDt and then converted to Ethereum a few days later, possibly in an attempt to prevent the token issuer from blocking them.

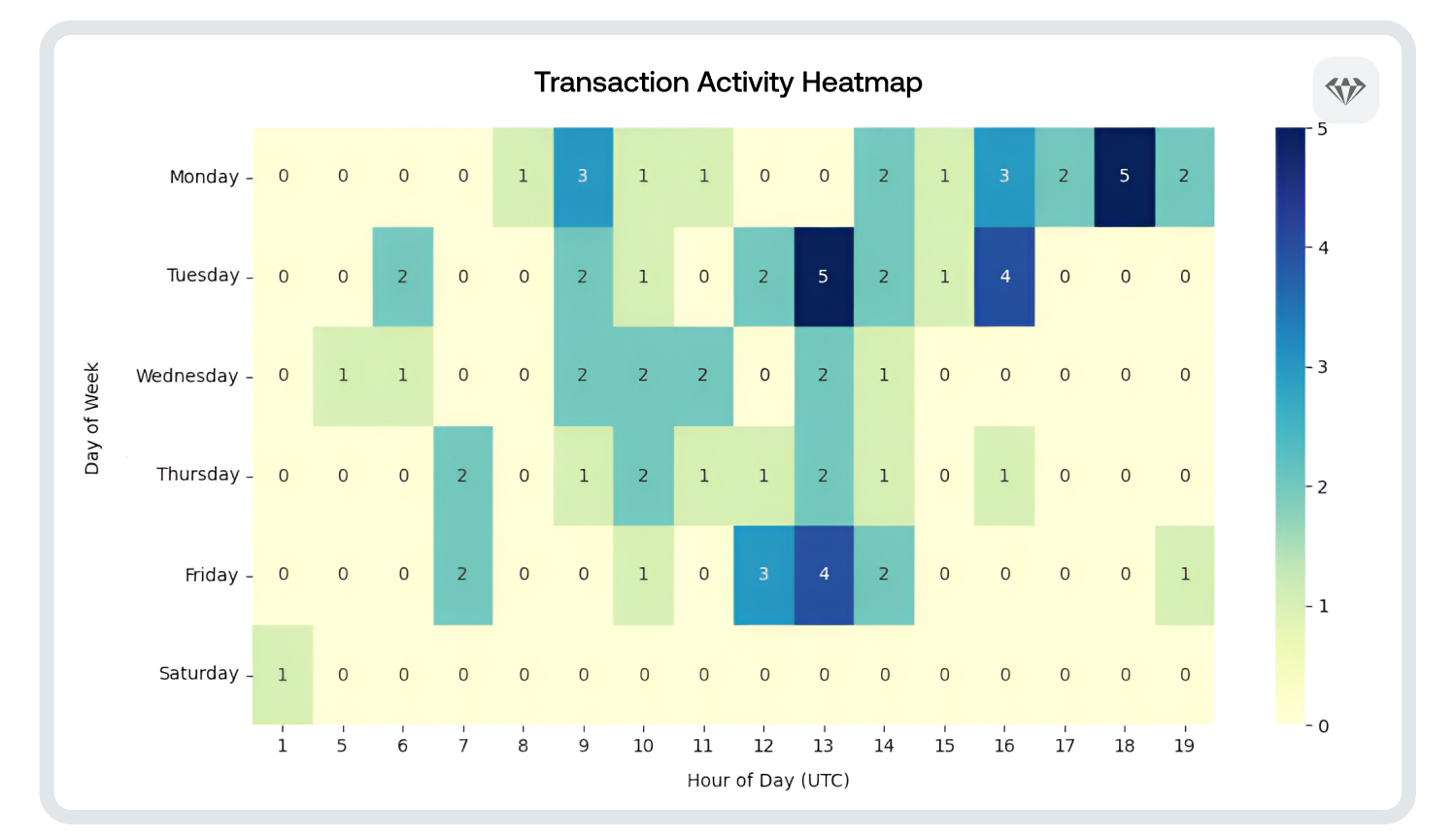

The 500,000 USDt received by the Safadi wallet likely came from a self-custodial wallet, which got almost all its funds from an institutional service provider. This address has significant activity, with over 14 million USDt being transacted between March and July 2024 before abruptly stopping. Temporal analysis shows it was most often operational during weekday office hours UTC time.

Above: Temporal analysis of self-custodial wallet address that sent funds to Al-Safadi. Darker areas of the chart show increased activity.

It cannot be determined if this wallet is under the control of the Syrian Intelligence services, but it does share the same broker – Saud al-Safadi. Separate research into Al-Safadi shows that he has significant connection to the Assad regime.

Destination of the confiscated funds

On both chains, funds were sent to the same exchange service provider. Based on other transaction activity, both chains are likely part of a nested service provider operating from that exchange. It cannot be determined on-chain if the nested service had permission to operate from the exchange.

Nested services may operate without the prior knowledge and consent of the host platform and often present an extremely high degree of risk to the operator, who may not be able to fully identify their client’s client.

Furthermore, it is likely that nested services are abused by criminals to suppress transaction monitoring and other compliance-related alerts, due to the relationship of trust between a permitted nested service and its host.

In these circumstances, the host service relies on blockchain analytics tools such as Crystal Expert, to help detect nested activity and identify suspicious sources of funds. These tools can also help expose weaknesses in any nested service’s onboarding and risk management processes to the main platform operator, which assists in keeping the blockchain safe, preventing or minimizing reputational damage, and avoiding costly legal ramifications.

Blockchain analytics as a key element of the Risk–Based Approach and Client Lifecycle

There are several important lessons for service providers to take from this case:

1. The association between the transaction and a service previously used by the Assad intelligence services.

The withdrawal from the institutional service to one wallet, which is linked to another wallet associated with the Assad regime, raises a red flag. This situation should typically prompt an urgent review of the client if the service provider was aware of this relationship and if it is ongoing. While it cannot be definitively concluded whether the wallet that received funds from the institutional provider is controlled by Assad’s intelligence services, it is clearly linked to a service they have used directly.

This illustrates the effectiveness of blockchain as a tool for transaction monitoring. Although the account may have been created using nominees and may have successfully deceived Know Your Customer (KYC) measures, the on-chain association should compel the service provider to investigate further, even after the fact.

2. The significance of localized data in high-risk regions

While many blockchain analytics tools boast extensive databases of various services, they often focus on highly visible, centralized exchange services. This approach risks overlooking less visible services which could pose higher risks.

In contrast, Crystal has concentrated on collecting data related to cash-for-cryptocurrency services, which have significantly gained popularity and often complement traditional financial services.

3. The value of hyperlocal intelligence

Identifying issues like these requires unique and hard-earned expertise and in-depth insights. By digging beneath surface-level media reporting and truly understanding high-risk environments, Crystal offers its users significantly deeper insights that can help shape business risk decisions.